The Nurses on Horseback and the People They Served is a three-part series covering the history of Frontier Nursing University. On the rugged hills of Eastern Kentucky, nurses earned trust by listening, learning from local families, and standing beside them in moments of illness, birth, and crisis. Over time, this collaboration improved health outcomes, reduced maternal and infant mortality, and strengthened the well-being of the community they served.

By Janet L. Engstrom, PhD, APRN, CNM, WHNP-BC, CNE, Anne Z. Cockerham, PhD, APRN, CNM, WHNP-BC, CNE, and Joanne M. Keefe, DNP, MPH, APRN, FNP-c, CNE

The centennial of the founding of the Frontier Nursing Service (FNS) offers the opportunity to reflect on the work of the nursing service and celebrate what was accomplished by the nurses and the community they served. Despite living and working in one of the most rugged, remote, and impoverished areas of the United States, their collaborative efforts significantly reduced maternal and infant mortality to lower than state and national rates. Their work also significantly improved child health and well-being, and the overall health of the community. Exploring how the nurses and their community accomplished these remarkable outcomes offers valuable lessons for health care providers today. This article reviews how the FNS built relationships and trust with the community and how together they created an effective and successful healthcare organization and university.

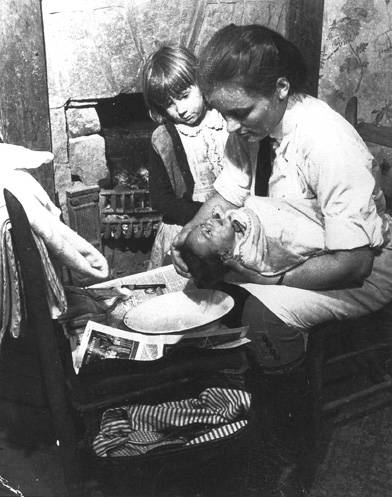

FNS nurse bathes a newborn baby while an older sibling observes the process.

Building Relationships and Trust with the Community

When the FNS decided to settle in Leslie County, the organization had to carefully build relationships and trust within the community. The process began by surveying the area to determine the existing health needs and resources. Mary Breckinridge spent the summer of 1923 riding through the most remote areas of the mountains, meeting families, talking to people about their health needs, and speaking with the local midwives who served the local families. Two years later, another survey was conducted to obtain a current census of the county and determine baseline birth and death rates. Two nurses were part of the survey team, and although their job was to complete the census, the head of the survey team noted that “it was perfectly wonderful how they managed to give advice, bandage sores, bathe wounds . . . while traveling rapidly from one house to another gathering statistics.”

This early demonstration of the nurses’ willingness to provide care regardless of the circumstances laid the foundations of trust in the community. Indeed, community members offered land, lumber, and labor to bring more nurses into the area.

Another important step in connecting with the community was the creation of the Kentucky Committee for Mothers and Babies to establish a plan for reducing maternal and infant mortality and improving public health. Once the plan was formalized, the next step was to develop the first local committee in Hyden, where the nurses would begin their work. The local committees were responsible for the nursing center in their area and played an important role in the operation of the center. This decentralized approach allowed community members to tailor the work to meet the specific needs of their area.

Local men carrying a person down the mountain. Extra men always came along so that the work could be shared by several people. Note the nurse alongside the patient and her horse being led behind the group.

After the committees were established, the FNS rented a building in Hyden to use as a clinic. The nurses planned to begin gradually, focusing first on converting the building into a clinic. However, many people came to the clinic and requested home visits for illnesses, injuries, and pregnancies. By the end of their first month, the two nurses had completed 561 visits for 233 patients and attended four births. Once the Hyden nursing center was established, the FNS needed to build district nursing centers to meet the needs of people in the more remote parts of the county. The building of these district nursing centers required extensive collaboration between the FNS and the community. Each community had to commit to building and supporting the nursing center, donating the land, materials, and labor for the center’s construction.

The first district nursing center was built at Beech Fork in 1926. Two nurses, Gladys Peacock and Mary Bristow Willeford, were assigned to oversee the construction of the nursing center. The nurses protested the assignment, stating that they knew nothing about construction, but Mary Breckinridge told them that they would learn. When they arrived at the construction site on the first day, the man in charge asked them what they wanted to do about the sills—the wooden beams that serve as the foundation of a building. Neither nurse knew what sills were, but Willeford respectfully asked the man what he would recommend doing about the sills. He explained how the sills should be positioned on the land, the type of lumber that should be used, and where the lumber could be located.

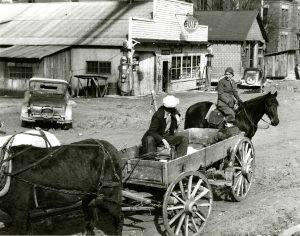

Local man transporting a sick mother to the hospital while the nurse stays close to the mother and holds her baby.

For every decision thereafter, the nurses responded with the same respectful question: “And what would you suggest, Mr. Hoskins?” The builder must have known that the nurses had no knowledge of construction, yet he walked them through the process, teaching them about construction and preparing them to build four more nursing centers.

The “learning” that Breckinridge had promised the nurses was achieved through their respectful acknowledgment of community members’ expertise and their willingness to accept guidance.

Beyond the work of building the nursing centers and volunteering to serve on local committees, community residents were often called upon to help the nurses transport sick or seriously injured patients to the hospital. Such transport often required carrying a person down or over a mountain using a makeshift stretcher, or placing someone in a boat and rowing to the hospital. Because the nurses always stayed with the patient, local people took care of the nurse’s horse and moved it from one location to another so the nurse could continue her work or return home once the patient was stabilized.

Carrie Belin is an experienced board-certified Family Nurse Practitioner and a graduate of the Johns Hopkins DNP program, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Georgetown University School of Nursing, and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She has also completed fellowships at Georgetown and the University of California Irvine.

Carrie Belin is an experienced board-certified Family Nurse Practitioner and a graduate of the Johns Hopkins DNP program, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Georgetown University School of Nursing, and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She has also completed fellowships at Georgetown and the University of California Irvine. Angie has been a full-scope midwife since 2009. She has experience in various birth settings including home, hospital, and birth centers. She is committed to integrating the midwifery model of care in the US. She completed her master’s degree in nurse-midwifery at Frontier Nursing University (FNU) and her Doctorate at Johns Hopkins University. She currently serves as the midwifery clinical faculty at FNU. Angie is motivated by the desire to improve the quality of healthcare and has led quality improvement projects on skin-to-skin implementation, labor induction, and improving transfer of care practices between hospital and community midwives. In 2017, she created a short film on skin-to-skin called

Angie has been a full-scope midwife since 2009. She has experience in various birth settings including home, hospital, and birth centers. She is committed to integrating the midwifery model of care in the US. She completed her master’s degree in nurse-midwifery at Frontier Nursing University (FNU) and her Doctorate at Johns Hopkins University. She currently serves as the midwifery clinical faculty at FNU. Angie is motivated by the desire to improve the quality of healthcare and has led quality improvement projects on skin-to-skin implementation, labor induction, and improving transfer of care practices between hospital and community midwives. In 2017, she created a short film on skin-to-skin called

Justin C. Daily, BSN, RN, has ten years of experience in nursing. At the start of his nursing career, Justin worked as a floor nurse on the oncology floor at St. Francis. He then spent two years as the Director of Nursing in a small rural Kansas hospital before returning to St. Francis and the oncology unit. He has been in his current position as the Chemo Nurse Educator for the past four years. He earned an Associate in Nurse from Hutchinson Community College and a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Bethel College.

Justin C. Daily, BSN, RN, has ten years of experience in nursing. At the start of his nursing career, Justin worked as a floor nurse on the oncology floor at St. Francis. He then spent two years as the Director of Nursing in a small rural Kansas hospital before returning to St. Francis and the oncology unit. He has been in his current position as the Chemo Nurse Educator for the past four years. He earned an Associate in Nurse from Hutchinson Community College and a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Bethel College. Brandy Jackson serves as the Director of Undergraduate Nursing Programs and Assistant Educator at Wichita State University and Co-Director of Access in Nursing. Brandy is a seasoned educator with over 15 years of experience. Before entering academia, Brandy served in Hospital-based leadership and Critical Care Staff nurse roles. Brandy is passionate about equity in nursing education with a focus on individuals with disabilities. Her current research interests include accommodations of nursing students with disabilities in clinical learning environments and breaking down barriers for historically unrepresented individuals to enter the nursing profession. Brandy is also actively engaged in Interprofessional Education development, creating IPE opportunities for faculty and students at Wichita State. Brandy is an active member of Wichita Women for Good and Soroptimist, with the goal to empower women and girls. Brandy is a TeamSTEPPS master trainer. She received the DASIY Award for Extraordinary Nursing Faculty in 2019 at Wichita State University.

Brandy Jackson serves as the Director of Undergraduate Nursing Programs and Assistant Educator at Wichita State University and Co-Director of Access in Nursing. Brandy is a seasoned educator with over 15 years of experience. Before entering academia, Brandy served in Hospital-based leadership and Critical Care Staff nurse roles. Brandy is passionate about equity in nursing education with a focus on individuals with disabilities. Her current research interests include accommodations of nursing students with disabilities in clinical learning environments and breaking down barriers for historically unrepresented individuals to enter the nursing profession. Brandy is also actively engaged in Interprofessional Education development, creating IPE opportunities for faculty and students at Wichita State. Brandy is an active member of Wichita Women for Good and Soroptimist, with the goal to empower women and girls. Brandy is a TeamSTEPPS master trainer. She received the DASIY Award for Extraordinary Nursing Faculty in 2019 at Wichita State University.  Dr. Sabrina Ali Jamal-Eddine is an Arab-disabled queer woman of color with a PhD in Nursing and an interdisciplinary certificate in Disability Ethics from the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). Dr. Jamal-Eddine’s doctoral research explored spoken word poetry as a form of critical narrative pedagogy to educate nursing students about disability, ableism, and disability justice. Dr. Jamal-Eddine now serves as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in UIC’s Department of Disability and Human Development and serves on the Board of Directors of the National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities (NOND). During her doctoral program, Sabrina served as a Summer Fellow at a residential National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) Summer Institute at Arizona State University (2023), a summer fellow at Andrew W. Mellon’s National Humanities Without Walls program at University of Michigan (2022), a Summer Research Fellow at UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute (2021), and an Illinois Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and related Disabilities (LEND) trainee (2019-2020).

Dr. Sabrina Ali Jamal-Eddine is an Arab-disabled queer woman of color with a PhD in Nursing and an interdisciplinary certificate in Disability Ethics from the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). Dr. Jamal-Eddine’s doctoral research explored spoken word poetry as a form of critical narrative pedagogy to educate nursing students about disability, ableism, and disability justice. Dr. Jamal-Eddine now serves as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in UIC’s Department of Disability and Human Development and serves on the Board of Directors of the National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities (NOND). During her doctoral program, Sabrina served as a Summer Fellow at a residential National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) Summer Institute at Arizona State University (2023), a summer fellow at Andrew W. Mellon’s National Humanities Without Walls program at University of Michigan (2022), a Summer Research Fellow at UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute (2021), and an Illinois Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and related Disabilities (LEND) trainee (2019-2020). Vanessa Cameron works for Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nursing Education & Professional Development. She is also attending George Washington University and progressing towards a PhD in Nursing with an emphasis on ableism in nursing. After becoming disabled in April 2021, Vanessa’s worldview and perspective changed, and a recognition of the ableism present within healthcare and within the culture of nursing was apparent. She has been working since that time to provide educational foundations for nurses about disability and ableism, provide support for fellow disabled nursing colleagues, and advocate for the disabled community within healthcare settings to reduce disparities.

Vanessa Cameron works for Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nursing Education & Professional Development. She is also attending George Washington University and progressing towards a PhD in Nursing with an emphasis on ableism in nursing. After becoming disabled in April 2021, Vanessa’s worldview and perspective changed, and a recognition of the ableism present within healthcare and within the culture of nursing was apparent. She has been working since that time to provide educational foundations for nurses about disability and ableism, provide support for fellow disabled nursing colleagues, and advocate for the disabled community within healthcare settings to reduce disparities. Dr. Lucinda Canty is a certified nurse-midwife, Associate Professor of Nursing, and Director of the Seedworks Health Equity in Nursing Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She earned a bachelor’s degree in nursing from Columbia University, a master’s degree from Yale University, specializing in nurse-midwifery, and a PhD from the University of Connecticut. Dr. Canty has provided reproductive health care for over 29 years. Her research interests include the prevention of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, reducing racial and ethnic health disparities in reproductive health, promoting diversity in nursing, and eliminating racism in nursing and midwifery.

Dr. Lucinda Canty is a certified nurse-midwife, Associate Professor of Nursing, and Director of the Seedworks Health Equity in Nursing Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She earned a bachelor’s degree in nursing from Columbia University, a master’s degree from Yale University, specializing in nurse-midwifery, and a PhD from the University of Connecticut. Dr. Canty has provided reproductive health care for over 29 years. Her research interests include the prevention of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, reducing racial and ethnic health disparities in reproductive health, promoting diversity in nursing, and eliminating racism in nursing and midwifery. Dr. Lisa Meeks is a distinguished scholar and leader whose unwavering commitment to inclusivity and excellence has significantly influenced the landscape of health professions education and accessibility. She is the founder and executive director of the DocsWithDisabilities Initiative and holds appointments as an Associate Professor in the Departments of Learning Health Sciences and Family Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Lisa Meeks is a distinguished scholar and leader whose unwavering commitment to inclusivity and excellence has significantly influenced the landscape of health professions education and accessibility. She is the founder and executive director of the DocsWithDisabilities Initiative and holds appointments as an Associate Professor in the Departments of Learning Health Sciences and Family Medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Nikia Grayson, DNP, MSN, MPH, MA, CNM, FNP-C, FACNM (she/her) is a trailblazing force in reproductive justice, blending her expertise as a public health activist, anthropologist, and family nurse-midwife to champion the rights and health of underserved communities. Graduating with distinction from Howard University, Nikia holds a bachelor’s degree in communications and a master’s degree in public health. Her academic journey also led her to the University of Memphis, where she earned a master’s in medical anthropology, and the University of Tennessee, where she achieved both a master’s in nursing and a doctorate in nursing practice. Complementing her extensive education, she completed a post-master’s certificate in midwifery at Frontier Nursing University.

Dr. Nikia Grayson, DNP, MSN, MPH, MA, CNM, FNP-C, FACNM (she/her) is a trailblazing force in reproductive justice, blending her expertise as a public health activist, anthropologist, and family nurse-midwife to champion the rights and health of underserved communities. Graduating with distinction from Howard University, Nikia holds a bachelor’s degree in communications and a master’s degree in public health. Her academic journey also led her to the University of Memphis, where she earned a master’s in medical anthropology, and the University of Tennessee, where she achieved both a master’s in nursing and a doctorate in nursing practice. Complementing her extensive education, she completed a post-master’s certificate in midwifery at Frontier Nursing University.

Dr. Tia Brown McNair is the Vice President in the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Student Success and Executive Director for the Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation (TRHT) Campus Centers at the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) in Washington, DC. She oversees both funded projects and AAC&U’s continuing programs on equity, inclusive excellence, high-impact practices, and student success. McNair directs AAC&U’s Summer Institutes on High-Impact Practices and Student Success, and TRHT Campus Centers and serves as the project director for several AAC&U initiatives, including the development of a TRHT-focused campus climate toolkit. She is the lead author of From Equity Talk to Equity Walk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education (January 2020) and Becoming a Student-Ready College: A New Culture of Leadership for Student Success (July 2016 and August 2022 Second edition).

Dr. Tia Brown McNair is the Vice President in the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Student Success and Executive Director for the Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation (TRHT) Campus Centers at the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) in Washington, DC. She oversees both funded projects and AAC&U’s continuing programs on equity, inclusive excellence, high-impact practices, and student success. McNair directs AAC&U’s Summer Institutes on High-Impact Practices and Student Success, and TRHT Campus Centers and serves as the project director for several AAC&U initiatives, including the development of a TRHT-focused campus climate toolkit. She is the lead author of From Equity Talk to Equity Walk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education (January 2020) and Becoming a Student-Ready College: A New Culture of Leadership for Student Success (July 2016 and August 2022 Second edition).